Last Updated on May 10, 2024

Greetings data junkies, ready for a surprise? Today we woke up to the news that WeChat had taken its’ analytics functionality to the next level with the addition of web analytics. That’s right, web analytics! Digital marketers have had access to in-app WeChat data for quite some time, but this takes things a step further.

WeChat’s previous data options were limited to interactions within the messaging interface but with the addition of web analytics, marketers can now analyze user interactions within WeChat’s web browser.

WeChat Web Analytics – Navigation Bar

WeChat Web Analytics – Navigation Bar

What data can be analyzed with WeChat’s web analytics?

Thanks to WeChat web analytics, official account owners can now see how users interact with their website & H5 files through the WeChat browser as well as when and where these interactions take place. These performance indicators are actually API calls such as “onMenuShareTimeline” or “downloadImage” but for the sake of easy understanding, we’ll refer to them as “interactions”.

Although it’s important to keep in mind that this is a brand new feature that will most probably be improved over time, the performance indicators it allows you to analyze are currently comprised of 39 on-page interactions and only one non-interactive indicator, page views.

What about the interface of WeChat analytics ?

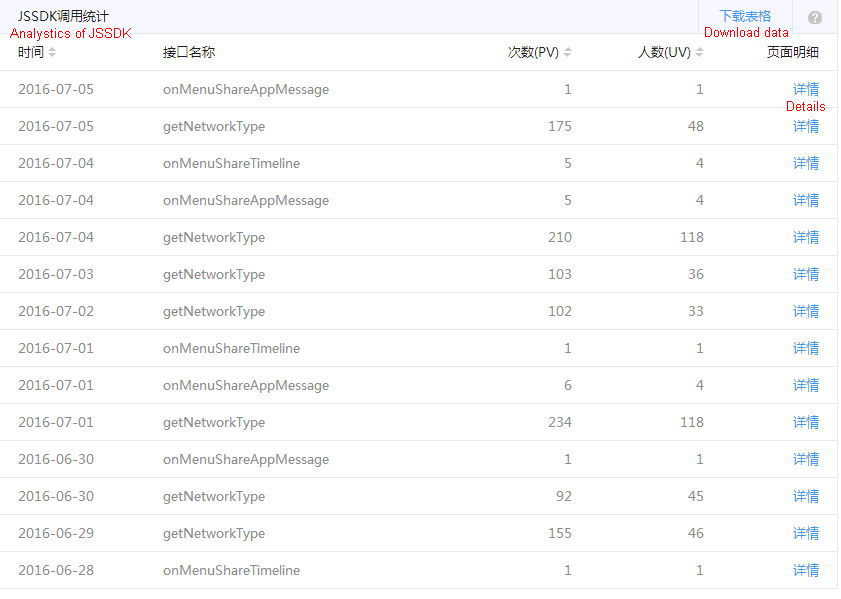

Just like Google Analytics, WeChat’s web analytics’ interface is split into 2 sections. The first section is a line graph which allows you to observe the frequency of a particular interaction over a 30, 15 or 7-day span while the second section underneath lists all interactions in chronological order.

This list of interactions also states the frequency of each interaction per day and the number of users that accounted for these interactions.

WeChat Web Analytics – Line Graph

WeChat Web Analytics – Line Graph

WeChat Web Analytics – Interactions Data

WeChat Web Analytics – Interactions Data

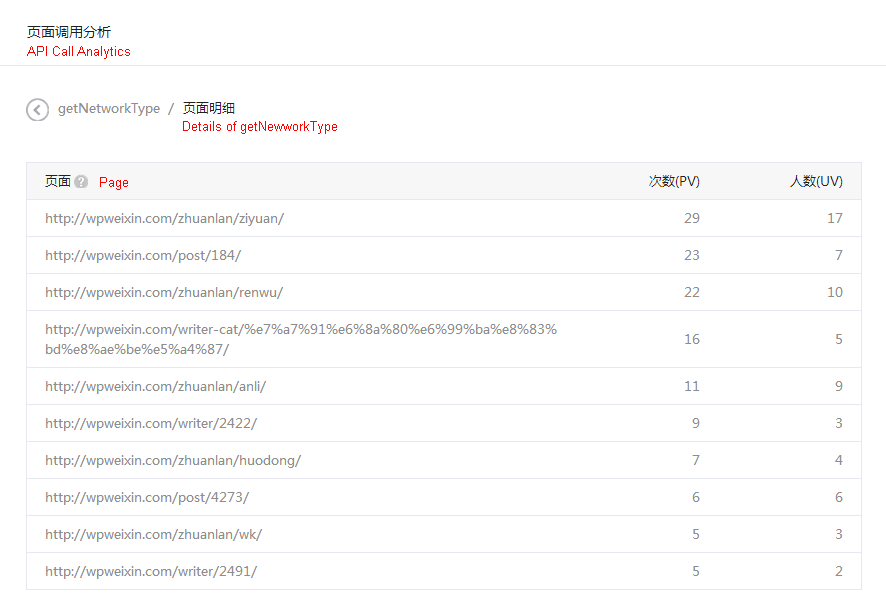

Clicking on “details” to the right-hand side of an interaction on a particular day gives you further data on that interaction such as the exact web pages or H5 files on which those interactions were made and the frequency of interactions per page. Sounds complicated? It’s not. Let’s say the initial interface lets you know that 25 unique users accounted for 50 image downloads on the 1st July 2016. Clicking on details will allow you to see on which pages these downloads were made, how many downloads were made per page and how many people downloaded images on each page on that day.

WeChat Web Analytics – Interactions Deep Data

WeChat Web Analytics – Interactions Deep Data

All in all, the web analytics feature is a welcome addition to WeChat’s data options and we can’t wait to try it out. Thanks to this extension, you can now track each and very interaction a user makes on your H5 files and use that analysis to improve your content. Data junkies, you’ve been served!

WeChat Web Analytics Screenshots Source.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

- wechat wallet missing

- sougoupinyin

- top social media in china

- baidubaike

- wechat features

- chinese search engines

- sogou keyboard

- tieba metal build

- wechat search

- chinese game app