On August 15, 2023, ShanghaiRanking Consultancy unveiled the highly anticipated 2023 Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU).

With over 2500 institutions thoroughly evaluated, this ranking isn’t merely a list—it’s a roadmap to academic excellence and cross-cultural engagement.

The 2023 ARWU press release coincides with a burgeoning trend: the growing interest among Chinese students to seek education beyond their homeland. As aspirations expand, foreign universities find themselves at a juncture of immense opportunity—to attract the next wave of ambitious minds from The Middle Kingdom.

For overseas schools, the ARWU rankings become more than a strategy; it’s a gateway into the thriving market of Chinese students seeking global education.

Showcasing Top-Ranked Universities

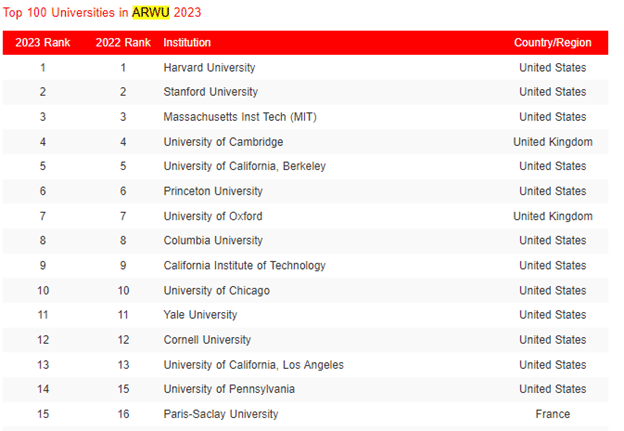

At the top of the 2023 ARWU stands Harvard University, a perpetual powerhouse that retains its number-one position for the 21st consecutive year. The elite trio is completed by Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), presenting themselves as the beacons of academic prowess and innovation for many years.

The remainder of the top 10 universities, including Cambridge, Berkeley, Princeton, Oxford, Columbia, Caltech, and Chicago, remain inside the leading academic circle that continues to shape the global educational landscape.

For foreign universities, being in this lineup is more than just a matter of prestige—it’s an opportunity to associate with academic excellence of the highest order. This academic recognition can become a magnet for Chinese students, attracting them toward a world-class education journey.

Source: Top 100 Universities in ARWU 2023 (Shanghai Ranking)

The Prestige of ARWU Rankings

To grasp the significance of the ARWU rankings, one must understand their historical significance and established credibility. For two decades, these rankings have set the standard for university excellence. The ARWU’s unwavering dedication to transparency and objectivity has solidified its reputation as a trustworthy and influential ranking system.

Moreover, these rankings don’t just exist for clicks; they have a persuasive impact on student decisions. Students worldwide are increasingly attuned to the allure of high-ranking institutions, and Chinese students are no exception.

As foreign schools vie for the attention of these students, a strong ARWU ranking becomes a compelling point of differentiation—a testament to excellence that speaks volumes to those seeking unparalleled education experiences.

Using ARWU Rankings to Enter the Chinese Education Market

The ARWU rankings act as more than just a symbol of excellence—they become a strategic tool for overseas universities to attract Chinese students. Crafting marketing strategies that spotlight the perks of studying at globally esteemed institutions opens doors for Chinese students to access unparalleled educational opportunities.

Employing personalized strategies that highlight the direct benefits of an ARWU-ranked institution can become a powerful catalyst for student enrollment. These strategies emphasize the quality of education and underline the prestige of being a part of a top-ranked institution.

Cultural Relevance of ARWU Rankings

The education market in China extends beyond academics. The ARWU recognition isn’t solely about numbers; it signifies an affinity with Chinese culture that values high-quality education for the younger generation.

Universities that have secured commendable ARWU rankings are positioned to provide an inclusive environment that harmonizes with their Chinese students’ cultural fabric and educational goals.

Ready To Dominate The Education Market In China? Get In Touch With Us Today!

As foreign schools strive to attract the wave of Chinese students seeking international education, ARWU rankings emerge as a strategic tool. Through the growing credibility and demand for international institutions, your time to be an educational industry leader in China begins now!

Equipped with deep insights into local preferences, cultural nuances, and evolving behaviors, we’re here to steer your business towards its peak potential.

Sekkei Digital Group excels in top-tier digital marketing and advertising campaigns for the Chinese Education Market. With seasoned experts, we can elevate your brand in the local business scene. Contact us today to begin your journey to success!