Last Updated on February 21, 2025

As an event occurring right after Chinese New Year and Valentine’s Day, some marketers may perceive the Lantern Festival as a less significant occasion for the local consumer market. However, did you know it wields enough cultural influence to spark substantial digital consumption in China?

In recent years, the Chinese Lantern Festival has demonstrated notable revenue growth across various sectors, including tourism, hospitality, food, beverages, and more.

As a foreign brand, how can you align this festival with your digital marketing campaigns? Here’s everything you should know about the Lantern Festival in China, as well as the strategies you can leverage.

What is the Chinese Lantern Festival?

The Chinese Lantern Festival is a national celebration in China that occurs every fifteenth day of the first lunar month of the Chinese calendar. Locally, it’s often referred to as “Shangyuan Jie,” with the literal translation of “Spring Lantern Festival.”

It has a history of around 2,000 years, dating back to the Eastern Han Dynasty. In ancient times, Chinese people referred to this grand festival as “Real Chinese Valentine’s Day.” Unmarried women and men used to view it as a chance to find romance.

However, as that part of the event died down and was redirected to the Qixi Festival, it’s now generally seen as an occasion to honor tradition and family togetherness.

Celebrations for the Lantern Festival in Taijiang County (Source: China Daily)

Beyond that, the Chinese Lantern Festival marks the end of the Spring Festival celebrations, the arrival of the first full moon of the year, and the beginning of the springtime season.

During this time, locals and businesses observe traditional Chinese culture, such as lion dance performances, lantern displays, and parades.

Eating tangyuan (湯圓) or yuan xiao (元宵) is also a popular tradition in China and other Asian countries. Many locals practice it to manifest good fortune during the celebration.

These sweet rice balls with different fillings are often incorporated as limited-edition offerings by foreign businesses trying to break into China’s F&B market to align their brands with local nuances.

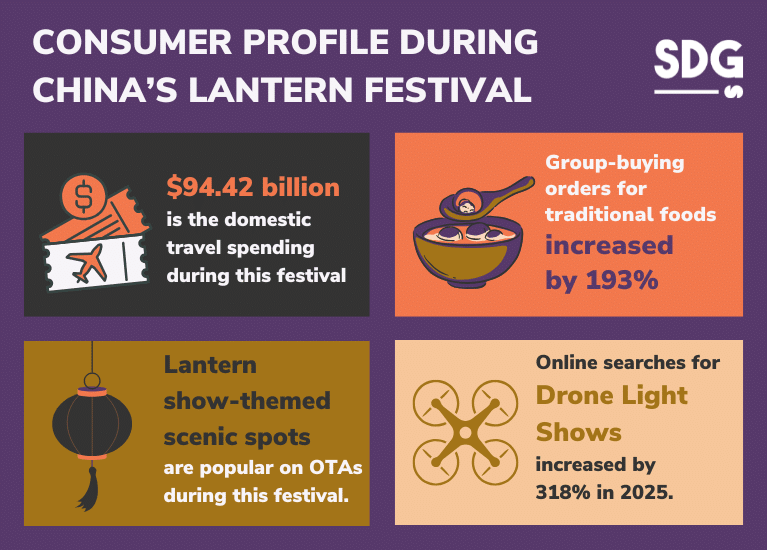

Consumer Profile During China’s Lantern Festival

China’s Lantern Festival often attracts the same consumer patterns as the Lunar New Year celebrations. However, with the unique theme of this occasion, local online shoppers tend to focus on searching and purchasing culturally relevant products and experiences.

Here are some statistics on how Chinese audiences engage online during the Lantern Festival in China:

- Domestic travel spending during the holiday reached 677 billion yuan (approximately $94.42 billion).

- Between January 29 and February 10, group-buying orders for traditional foods like yuan xiao (glutinous rice) increased by 193%.

- Online searches for drone light shows on the Meituan travel platform increased by 318% in 2025.

- Bookings for lantern show-themed scenic spots on Qunar witnessed a nearly 20% increase compared to last year.

How did Chinese Consumers Celebrate the Lantern Festival in 2025?

● Online Travel Bookings

With the lunar calendar filled with back-to-back traditional holidays during the first quarter of the year, it seems like the local tourists didn’t wait long after the Spring Festival to pack their bags again.

According to figures cited by the Global Times, bookings on Qunar for lantern-themed tourist destinations increased roughly 20% year-on-year. Notable hotspots included iconic lantern fairs in Zigong (Sichuan Province), Yuyuan Garden in Shanghai, and the historic Qinhuai lantern fair in Nanjing (Jiangsu Province).

During the Chinese Lantern Festival, hotels in these cities saw a parallel uptick, with reservations rising by over 10% compared to last year.

Qinhuai Lantern Fair in Nanjing (Source: China Daily)

● Group Buying and Family-Oriented Purchases

Group-buying platforms continued to experience high traffic during the Lantern Festival. Douyin’s data showed that group-buying orders for traditional festival treats soared by 193% more than last year.

Family reunion packages, special meal deals, and discounted tickets to local attractions were also popular during this festival. This trend reflects a strong preference for affordable, collective purchase options that unite family members.

Source: Pressfoto on Freepik

● Tech-Driven Lantern Festival Celebrations

During major festivals like Chinese New Year, the tradition of watching fireworks is slowly getting taken over by drone light shows. The same can be said about China’s Lantern Festival.

Based on Meituan Travel’s data, searches for drone shows skyrocketed by 318% year-on-year in the week leading up to the Lantern Festival.

On top of that, Dianping (a popular city guide and lifestyle review platform) also noted an 11-fold surge in searches for cultural heritage activities that used cutting-edge tech, such as 3D holographic projections.

The use of modern technologies during this festival attracted young, tech-savvy Chinese tourists looking for fresh holiday experiences.

Source: Global Times

● Extended Spring Festival Shopping Spree

The online shopping frenzy did not end with the Chinese New Year. It continued well into the Lantern Festival. Retailers benefited from a long-tail effect this year as consumer enthusiasm extended beyond the core Spring Festival dates.

Sales of lanterns and decorative items on platforms like Taobao and JD.com rose significantly, with Meituan reporting a 130% increase in lantern purchases compared to 2024.

Best Marketing Campaigns for the Chinese Lantern Festival

1. Promotions of Event-Themed Products on Social Media

Chinese festivals are golden marketing opportunities to localize your brand. By offering products related to the celebration, chances are you’re also catering to the real-time needs of your target consumers.

For example, just last year, Starbucks released a limited-edition Lantern Festival treat: Luck Savory Latte. This drink is made with the popular delicacy Dongpo pork-flavored syrup and dried pork toppings.

This is an attempt to localize the global brand’s menu and curb the growing competition with Luckin Coffee, which is popular for its offerings integrated with domestic ingredients.

Topic section for “Starbucks respond to releasing red-braised pork latte” on Weibo

This move allowed Starbucks to align its offerings with traditional Chinese tastes and generated significant buzz on Chinese social media platforms. While the unique flavor drew mixed reactions, it made more local consumers curious about Starbucks’ Lantern Festival offerings.

On Weibo, the topic “Starbucks respond to releasing red-braised pork latte” or #星巴克回应推出红烧肉拿铁# gained over 27 million views. This amount of social media traffic has led to the hashtag reaching the top 23 spot on the hot trending search list.

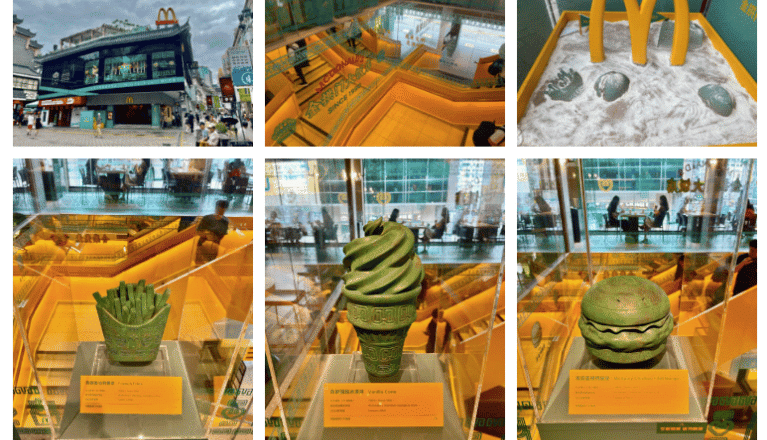

2. Co-branding with Traditional Chinese Establishments

Unlike previous iterations, which focused solely on nostalgic aesthetics, this new guochao trend strongly emphasizes cultural authenticity. Museums, temples, and historical landmarks have become perfect co-branding partners for global businesses eager to connect with Chinese consumers.

Last year, McDonald’s collaboration with the Sanxingdui Museum, a renowned archaeological site in Sichuan, was a standout example of co-branding. They introduced a Sichuan hotpot-flavored McSpicy burger, packaged in a striking bronze-colored design inspired by Sanxingdui’s iconic relics.

Source: Dao Insights

The campaign extended beyond product innovation. A series of micro dramas on Douyin depicted office workers humorously wearing gold foil masks, similar to those found in the Sanxingdui ruins, while enjoying their meals.

These videos garnered quite a large audience on the platform, with one of the episodes generating 42,000 likes.

KFC also has a long-standing co-branding history in the Chinese market. Since 2020, the fast-food chain has worked closely with the Palace Museum in Beijing. For major festivals like the Lantern Festival and Chinese New Year, they’ve released packaging inspired by Qing Dynasty calligraphy.

3. E-Commerce Sales Events

While the Chinese Lantern Festival isn’t traditionally associated with the same level of shopping frenzy as Singles’ Day (11.11) or the 618 Festival, major e-commerce platforms have capitalized on it in recent years.

E-commerce giants like Tmall and JD.com often launch flash sales featuring exclusive, festival-themed products. These offers range from decorative items to traditional snacks, creating a sense of urgency that boosts sales and deepens the cultural connection with the festival.

With these e-commerce platforms integrated with social media features, brands can leverage video and live-streaming content to trigger relevant user engagements.

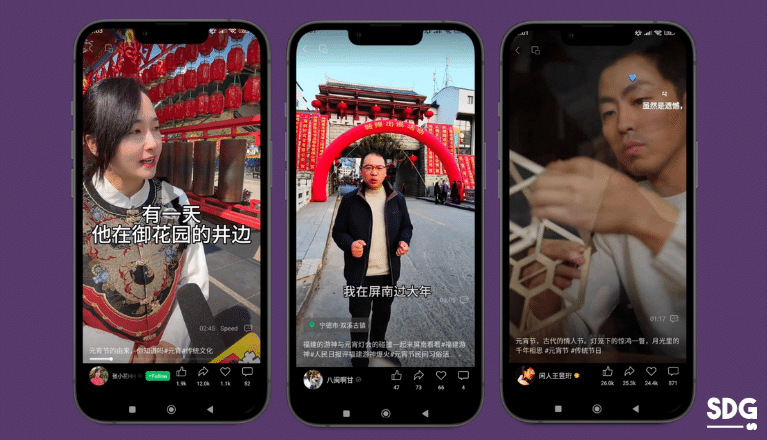

4. Collaborations with KOLs and KOCs

KOLs and KOCs have built strong, loyal followings by sharing genuine experiences and opinions. During the Lantern Festival, a time filled with cultural symbolism and personal celebration, audiences are more likely to engage with content that feels real and heartfelt.

Their endorsements can transform a marketing message into a shared cultural narrative, resonating on a personal level with consumers. This authenticity often translates into higher trust, increasing the chances of successful consumer engagement.

Compared to traditional advertising, influencer marketing with KOLs and KOCs often provides a better return on investment, especially during specific seasonal events.

Their targeted approach means marketing budgets are more effectively spent on reaching consumers already interested in cultural and festive content.

KOLs and KOCs posting about the Chinese Lantern Festival on WeChat

Your Trusted Digital Marketing Partner in Mainland China!

The Chinese Lantern Festival is among the many traditional events local consumers celebrate in China. And while it’s not as massive as other major holidays within the country, it can build momentum for foreign brands to generate local visibility and engagement.

You may also want to read:

At Sekkei Digital Group, we understand how crucial Chinese festivals are to your digital marketing calendar. With our extensive industry experience and expertise in China’s digital ecosystem, we can help your brand reach relevant audiences and establish an authority in the local business landscape.

Whether you intend to collaborate with influencers or launch event-themed products on e-commerce platforms, we have all the digital solutions you need. Get in touch with us today, and let’s start planning your Chinese digital marketing calendar.